ARTE & TRADICIÓN

RARÁMURI

RARÁMURI

ART & TRADITION

TAMÓ

RALÁMULI

NEWÁLA WIKÁ NAMÚTI

Arte y Tradición Rarámuri

Arte/Artesanía debate del quehacer de la humanidad como expresión social. En qué momento el arte manifiesta la crítica y la artesanía lo utilitario; en qué momento el arte es hermoso o grotesco y la artesanía es ornamental, pero de igual manera con una exaltación estética, ¿qué fibra de la sensibilidad del ego de las artes es atentada al momento de llamar algo arte o artesanía?

Es certero que está abierto a debate, sin embargo en la expresión humana y su quehacer, el propósito es el de transferir información de la mente a un objeto ya sea pintura, escultura, cerámica, textiles u otras diversas manifestaciones de creación cuya finalidad va más allá de revelar algo y compartir el conocimiento. Es nuestro interés mostrar piezas que, en su contexto utilitario como arte puro de las culturas originarias, se vuelven valiosas y contemplativas. Esta exposición pretende acercar al espectador al patrimonio cultural de nuestro estado, ofreciéndoles, una muestra de tradiciones, objetos y textiles, que demuestran el valor de un contenido profundo en el carácter de la visión artística, estos cuidadosamente seleccionados para representar en esta ocasión a la etnia Rarámuri. A través de una colección de fotografía documental en torno a sus festividades y tradiciones, así como la apuesta de faldas y la arihueta, los textiles naturales tradicionales como faldas, la lana, los trajes masculinos, paliacates, la cestería, ollas e instrumentos musicales, algunas de estas piezas participantes en el concurso de Arte Popular FODARCH en Sisoguichi, cuya visión es darle un motivo artístico a las productos utilitarios.

El arte popular nos muestra en esta exposición un reflejo de la visión del arte Rarámuri, comunicando de manera honesta su tradición, sus vivencias, su colorido y sus materiales, esperando dejar en el inconsciente colectivo la magia de un pueblo que a trascendido a los años y se mantiene fuerte ante la adversidad del tiempo.

Rarámuri Art and Tradition

Art/Craftwork discussion of the doings of humanity as social expression. At what point does art manifest critique and craftwork the utilitarian; at what point is art beautiful or grotesque and handicraft ornamental, but in the same way an aesthetic exaltation, ¿which fiber of the sensibility of the ego of arts is threatened when calling something art or craft?

It is certain that it is open for debate, however in human expression and its work, the purpose is to transfer information from the mind onto an object, be it painting, sculpture, ceramics, textiles or other diverse manifestations of creation whose purpose goes beyond revealing something and sharing knowledge. It is our interset to show pieces that, in their utilitarian context as pure art of native cultures, they become precious and contemplative. This exhibition aims to bring the viewer closer to the cultural heritage of our state, offering a sample of traditions, objects and textiles, that demonstrate the value of a deep content in the character of artistic vision, carefully selected to represent on this occasion the Rarámuri ethnic group. By means of a collection of documentary photography about their festivities and traditions, as well as skirt betting and arihueta, traditional natural textiles such as skirts, wool, men's suits, bandanas, basketry, pottery and musical instruments, some of these pieces participated in the FODARCH Popular Art contest at Sisoguichi, whose vision is to give an artistic motif to utilitarian items.

Popular art shows us in this exhibition a reflection of the vision of Rarámuri art, honestly communicating their tradition, their lifestyle, their color and materials, hoping to leave in the collective unconscious the magic of a a people that has trascended the years and remains strong against time's adversity.

Tamó ralámuli newála wiká namúti

Artesania tamó newalá ko machiwá wichúli japirika we kaniila ke re newá alí nijá. Chu riko jónsa a mawále artesania niila; chu riko jónsa we chimami ju o we kaniilalami ali artesanili ko we natéami niili o wichálimi niili, alí ayéna cho chimámi ju, ¿Pili ke ta bewálami ju tamó newála mápuali re’wáli arte o artesania?

Je’ni ko suwíni jápirika aniwá ra’ícha. Jápirika tamó we kaniilami ju alí churía newá, newámale jápiria náta ke re mo'óchi bilé namúti ke re pinturi, we’chóli newárami ke re, bitóli, bo'osali kite newárami wikabé namúti japiriká tamó newá riko pe aminámi nokísabo re newáse alí ayéna cho nijáse jápiria tamó machimi ju. Tamó ko we kaniili jápi tamó newáli ju, we natéami ju arte jápi tamó ralámuli newáli ju, we abila natéami ju ali enéliami. Iké ko ju jápiria machíme ulubéli nalí patrimonio cultural niila je’naí Estado, nija, énera tamó niili tradiciones, namúti li bo’osali kíte newárami, jápirika machíme we natéami ju tamó newála nalí visión artístika niila, iké kiili niila epérumi jípi jápi eneríma re ralámulita niila. Retatártumi jápi alí omáwi tradisiones, re’e ariwéta, sipuchí newárami jápi tamó niili ju, bo'osali, rejói niili napáchi, napóla, walí, sekóli alí chapáleki semélemi, iké namúti newálami ko re’e biléni re’emi ‘Arte Popular FODARCH’ anelíami na Sisoguichi, iké ko we natéami ju a’li enérele taame niila.

Arte Popular ko enéra ralámuli, ru’eya tradisioni niila, jápiria eperé, kolóri ali namúti, bo’éya alí rewéya jápuali machiwaami ju ya nilumi niila, we iwérika chukú jípe.

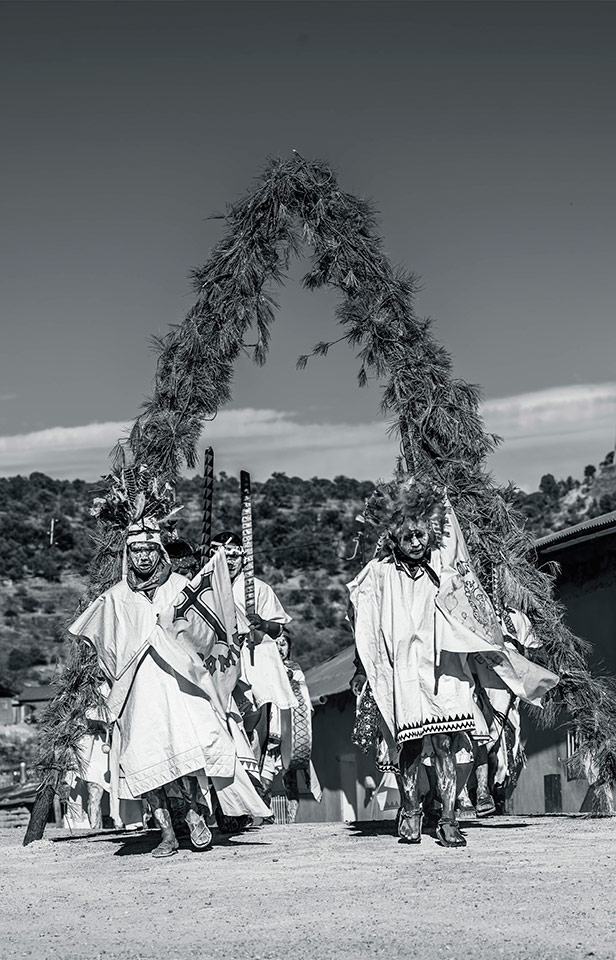

Semana Santa Rarámuri

Fotografía de Lorena Borja Rascón

Rarámuri Holy Week

Photographs by Lorena Borja Rascón

Nolirúachi Rarámuri

Retráti Lorena Borja Rascón

GobernadoresSiríame

GovernorsSiríami

Autoridad durante la Semana SantaAlapérusi or monarch

Authority during Holy WeekAlapérusi

Igúsuhua mapuyena Norírahuachi

En la profundidad de las barrancas de la Sierra Madre Occidental, en el estado de Chihuahua habitan seres celestes, seres de luz, pilares del mundo: los Rarámuris, hijos de Onorúame – Eyerúame.

Deep in the ravines of the Sierra Madre Occidental, in the state of Chihuahua, inhabit celestial beings, beings of light, pillars of the world: the Rarámuris, children of Onorúame – Eyerúame.

Amí relétu ulí je’naí estado de Chihuahua eperé tamó, je’naí kawírili: tamó Onolúame-Iyeluame kuuchi.

La danza es una forma de caminar en otras dimensiones, en otros territorios: en los territorios celestes e invisibles.

Dance is a way of walking in other dimensions, in other territories: in celestial and invisible territories.

Tamó niili omáwalemi ko ju pe aminábi nokisilemi, wiche jaréna kawiwálachi eperé ke re.

Carlos Montemayor

procesión de la Virgen María y JesúsPillars of the World

procession of Virgin Mary and Jesus Je’naí kawírili

Pies ligeros que danzan, que giran, que vuelan; de no hacerlo el Dios Sol dejará de correr por la bóveda celeste y su luz se apagaría como en los tiempos primigenios.

Light feet that dance, that turn, that fly; otherwise, the Sun God would stop running across the celestial vault and his light would go out as in ancient times.

Walíname ronóli awíma, kulí, i’níma; jápi alí ke newásu omáwali ke kulíma rayéni choime jápiria ná tarija.

“Me aguanto el frio de la noche y me río de la tierra helada. ¡A veces parece que la oscuridad no termina y que las fuerzas del mal me van a ganar!”

“I endure the cold of the night and laugh at the frozen earth. Sometimes it seems that the darkness does not end and that the forces of evil are going to defeat me!”

“Ne ko anáchi ruláma rokó alí achiá we’erili ruláchi. ¡Siní kaachi ke la suníka re chónachi alí ko cháti we niuraka re!”

Danza Pascol: los que derrotan a las fuerzas oscuras con sus danzas.

Pascol Dance: those who defeat the dark forces with their dances.

Jápiria we iwéliga awí chónachi.

“Nosotros hacemos mucho tesgüino y danzamos mucho para tener contento a Onorúame.”

“We make a lot of tesguino and dance a lot to keep Onorúame happy.”

“Tamó ko we ulú súji newámi ju jápiria omáwabo aló awíbo jápiria Onolúame kaniilima.”

Lorena Borja Rascón

Fotografías digitales

2023

30cm × 46cm (horizontales) y 46cm × 30cm (verticales)

Lorena Borja Rascón

Digital photographs

2023

12" × 18" (horizontal) y 18" × 12" (vertical)

Lorena Borja Rascón

Retráti

2023

30cm × 46cm (bití) y 46cm × 30cm (jahua)

Al ver una artesanía, no dejo de sentir admiración y maravillarme por todo el trabajo que implica realizarla. No hay diferencia entre un tamaño u otro, cada una tiene su esfuerzo, dedicación y sus complicaciones para lograr terminarla. Cada trabajo trae una historia detrás, pensar en las manos que la realizan y como quizás sienta un dolor o cansancio, pero continúan. Me llena de emoción ver como cada vez somos más los que apreciamos la artesanía y los que la vemos por lo que es; una obra de arte. No hay ninguna pieza exactamente igual, aunque las manos sean las mismas.

Nuestra artesanía cada vez es más conocida fuera del estado y en otros países. Brilla en el mundo y lo hace con luz propia. Espero que cada vez nuestros artesanos sean más vistos como los grandes artistas y maestros que son.

Al escuchar la palabra artesanía pensamos en flores bordadas, en un rebozo, pero el voltear a ver la artesanía chihuahuense, vemos más que eso, vemos los colores de nuestro gran paraíso, de la sierra, del cielo, del barro... Al verla sentimos paz, serenidad y nos enseña a valorar lo que tenemos y lo que nos toca cuidar.

Joni Barajas González

Directora de Fomento y Desarrollo Artesanal del Estado de Chihuahua

When I see a craft, I can't stop feeling admiration and marveling at all the work involved in making it. There is no difference between one size or another, each one has its effort, dedication and its complications to finish it. Each job brings a story behind it, think about the hands that perform it and how you may feel pain or tiredness, but they continue. It fills me with emotion to see how more and more of us appreciate crafts and see it for what it is; a work of art. There is no piece exactly the same, even if the hands are the same.

Our craft is becoming more popular outside of the state and in other countries. It shines in the world and it does so with its own light. I hope that our artisans are increasingly seen as the great artists and teachers that they are.

When we hear the word crafts we think of embroidered flowers, in a shawl, but when we turn to see Chihuahuan crafts, we see more than that, we see the colors of our great paradise, of the mountains, of the sky, of the clay... When we see it We feel peace, serenity and it teaches us to value what we have and what we have to take care of.

Joni Barajas González

Director of Fomento al Desarrollo Artesanal del Estado de Chihuahua

(Office of Promotion and Development of Handicrafts of the State of Chihuahua)

Jápiali enéya bilé artesaniri, ke rewé eneyá alí kalá chimámi ju jápi tamó newá. Ke siwiná lámi ju pe wéli ali kuuchi pe ichópi lámi ju, we iwéria newáliami ju, we lináti suwínilemi. Tamó nochári ko namúti toyá ya nirúami, náta sekári jápi tamá newáli ayéna cho o’kó alí risía, pe abila ária ‘a noká newá. We kaniila pe a wikabé ju jápi alí kaniila newayá artesanila alí enéna churia a ko ba; bilé arte. Ke nirú bilé namúti ichópi lámi, ali ko pe ichópi wéli sekáti newálami ke re.

Tamó niili artesaniri ko wichúri machiwaami machími Estado ali wiche bileni paisi. We rapála kawirili alí abóni newála. Pe ‘a boyébo jápi artesaniri newámi ju machiméa we jibenami ko ba alí binílami.

Alí jípi artesaníri niila náta kimili sewarítumi niila, bilé rebósi, alí kulícha enéya artesaniri Chiwawénse, wekabé namúti enébo, enébo wiká kolóri je’naí wichimóba, kawiwaalachi, alí repá siyónachi, wechóli… alí enéya tamujé we kaniili, kiili alí binirá jápi tamó niwí alí tibú.

Joni Barajas González

Directora de Fomento al Desarrollo Artesanal del Estado de Chihuahua

Instrumentos Musicales

Musical Instruments

Táami Namútali

Tambor ceremonial

Madera y cuero

2023

⌀58cm

Madera y cuero

2022

61cm

Tambor ceremonial

Madera y cuero

2022

⌀65cm

Palo de lluvia

Madera y semillas

2023

53cm

Arpa

Madera y piel

2023

70cm × 90cm

Chapareque

Madera, alambre y piel

2022

91cm

Madera y semillas

Sonaja de huaje

Huaje y semillas

2022

50cm

Matraca de guacamaya

Madera

2023

32cm

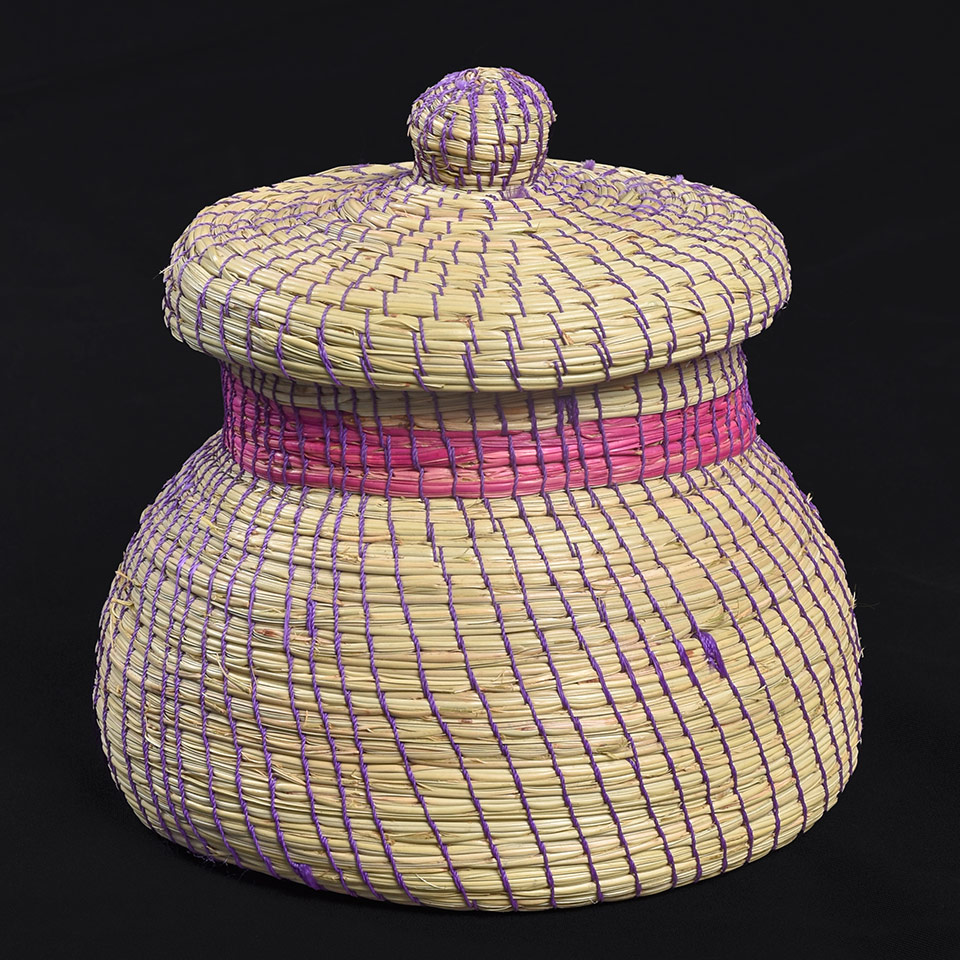

Guares

Baskets

Huari

Guare gigante petaca con tapa

2023

Palma tejida

Giant basket with top

2023

Woven sawgrass

Watobé (imuli)

2023

Kulú

53 cm × ⌀50 cm

Guare gigante petaca con picos

2023

Sotol tejido Giant spiked basket with top

2023

Woven sotol Watobé (imuli)

2023

Guare gigante petaca con tapa

2023 Giant basket with top

2023 Watobé (imuli)

Guare sotol con tapa tipo corona

Sotol basket with crown top

Umuli

2023

10cm × ⌀22cm

Guare gigante petaca con picos

2023 Giant spiked basket with top

2023 Watobé (imuli)

2023

Guare con tapa tipo ocoxal

2023

Tejido de pino

Basket with top

2023

Pine Umuli

2023

Okó 18cm × ⌀18cm

Guare con tapa tipo ocoxal

2023

Pino

Basket with top

2023

Pine Umuli

2023

Okó 18cm × ⌀23cm

Guare tipo jarrón con tapa

2023

Pino

Vase-type basket with top

2023

Pine Umuli sikolí

2023

Okó 15cm × ⌀15cm

Guare jarrón grande

2023

Sotol tejido

Large vase-type basket

2023

Woven sotol

Watobé sikolí

2023

37cm × ⌀30cm

Guare jarrón grande

2023

Sotol tejido

Large vase-type basket

2023

Woven sotol

Watobé sikolí

2023

35cm × ⌀26cm

Guare jarrón grande

2023

Sotol tejido

Large vase-type basket

2023

Woven sotol

Watobé sikolí

2023

39cm × ⌀33cm

Guare con tapa

2023

Pino

Basket with top

2023

Pine Umuli

2023

Okó 12cm × ⌀16cm

Guare de pino tipo cenicero

2023

Pino, sotol y palma

Ashtray type basket

2023

Pine, sotol and sawgrass

Wali napisó

2023

17cm

Guare cenicero

2023

Sotol tejido

Ashtray type basket

2023

Woven sotol

Wali napisó

2023

19cm × ⌀36cm

Guare jarrón

2023

Palma tejida

Vase-type basket

2023

Woven sawgrasssotol

Wali sikolí

2023

Kulú

29cm × ⌀22cm

Guare con tapa tipo ocoxal

2023

Pino

Basket with top

2023

Pine Umuli

2023

Okó 18cm × ⌀29cm

Ropa

Clothing

Chiní

Vestido rosa con grecas negras;

huaraches y paliacate negro

Vestido naranja con grecas blancas-negras

con faja de estambre

Vestido de la baja (falda verde y blusa rosa)

Traje camisa roja; jorongo de manta, collera, tagora, huaraches y bolsa blanca en forma de camisa

Vestido azul marino con grecas rojiblancas;

rebozo, bolsa, collera y aretes de chaquira

Traje de hombre color blanco con grecas rojas

Vestido de la baja (azul con flores)

Traje hombre camisa roja con grecas verdes, blancas y rojas; huaraches, faja y tagora

2022

200cm

2022

240cm

Barro

Clay

Wechóli

Vaca alacancía

Barro

2023

23cm × 28cm

Figura humanoide con manos

Barro y manos

2023

25cm × 20cm

Figura con forma cabeza de venado

Barro

2023

14cm

Jarra con tapón

Barro

2023

30cm

Olla con asas y pintura

Barro

2023

39cm × 39cm

Pato con tapa

Barro

2023

24cm × 25cm

Pareja rarámuri

Barro

2023

15cm × 19cm

Olla de cuatro bocas

Barro

2023

30cm × 20cm

Olla corrugada con base

Barro

2023

63cm × 50cm

Barro, madera y piel

2023

55cm

Barro, madera y piel

2023

140cm × ⌀50cm

Barro, madera y piel

2023

74cm

Objetos diversos

Diverse objects

Calúmati namuti

Víbora de sotol

Fibras de sotol

2023

45cm

Víbora de sotol

Sotol tejido

2023

52cm

Muñeca de corteza con telar

Madera y textil

2023

20cm × 20cm

Escalera

Madera y cuero

2022

153cm × 40cm

Rosario

Barro

2023

70cm

Ariweta, apuesta de faldas

Rarajípari (carrera de hombres) que significa en rarámuri rará (pie) y pa (arrojar,) y Ariweta Rowera (carrera de las mujeres). La carrera de bola y ariweta, se trata de una carrera en la que se representan los conocimientos y prácticas de la cultura rarámuri, la cosmovisión y el entorno.

Esta carrera se puede organizar en cualquier época, la mayoría de ellas se concentran en la época del año que resulta más propicia, para su desarrollo, entre el verano y otoño, época en la que hay más tiempo libre, menos dedicación a la tierra, no hace tanto calor ni frío por la noche y la lluvia refresca y humedece el ambiente.

La carrera de bola y ariweta se conforma por dos equipos, máximo de 8 integrantes cada uno de los equipos, se suele competir con pueblos vecinos, de rancherías cercanas e incluso de la misma comunidad, las carreras tienen una duración entre 24 y 30 horas con 180 a 200 km en los hombres y entre 8 y 15 horas para las mujeres, estas se pueden empezar como a las 6 de la tarde y terminar a media noche o hasta en la mañana del día siguiente.

La carrera se juega lanzando una pelota de madera, la cual es realizada por ellos mismos. La ariweta es un anillo que se lanza con una varilla y se juega con la misma dinámica que la carrera de bola. Al finalizar la carrera, los chokéames reparten las apuestas, en éste caso, las faldas de las mujeres, las cuales son valiosas por la cantidad de trabajo que conllevan.

Ariweta, skirt betting

Rarajípari (men's race) which means in rarámuri rará (foot) and pa (throw) and Ariweta Rowera (women's race). The ball and ariweta race is a race in which the knowledge and practices of the Rarámuri culture, worldview and environment are represented.

This race can be organized at any time, most of them are concentrated in the time of the year that is most propitious for their development, between summer and autumn, a time when there is more free time, less dedication to the land, It is not so hot or cold at night and the rain cools and humidifies the environment.

The ball and ariweta race is made up of two teams, a maximum of 8 members each of the teams, they usually compete with neighboring towns, nearby ranches and even from the same community, the races last between 24 and 30 hours with 180 to 200 km for men and between 8 and 15 hours for women, these can start around 6 in the afternoon and end at midnight or even in the morning of the following day.

The race is played by throwing a wooden ball, which is made by them. The ariweta is a ring that is thrown with a rod and is played with the same dynamics as the ball race. At the end of the race, the chokéames distribute the bets, in this case, the women's skirts, which are valuable due to the amount of work involved.

Ariweta, sipúcha nijálemi

Ralajípari ju ralámuli “ralá” (ronówi) ali (rité) li ariwéta ko ”rowéla”. Ralájipa ali rowé, iké ju jápi machí re’é riko re’émi machiami ralámulita niila, ke tási ratá li ruluwá rokó alí bukíko pe sepéchi alí iminá.

Iké re'emimi ko pe chuwé remimí ju, we a'la kuwéwachi, alí jápi ke me namúti oláchi, ke we'eri nocháchi, ke me ratáchi alí rulaachi rokó alí bukí sepécha alí miná.

Ralajípari alí rowéri okuá niila ju, osanaó niila biléna, nasaita wiché jaréni eperémi ujá, mulubé epermi, ike re'emimiko anachi osamako nao hora li biasa mako hora li bile sienti osanaos makoí alí okuá sienti kilometro ukuri ko osánao alí malí makoí hora iwé ko, alí ko re'emimi ko chotá ali kiti usáni hora alí suwíni nasípa rokó alí amó be’alina.

Iké ko re’e ralípa ju kapólami, aboi newála. Ariweta ko sitúlami ju re’emimi ju jápiria komátarija, alí ma sunísa ko re’e chokéami rojáchi japi ikí nijáli namúti, sipúcha umukí niili, jápiria we natéami ju.

Carrera de Bola, video de German Silva en YouTube.